For much of its history, Indian screen music was designed to command attention. Songs arrived like cinematic punctuation marks, vivid, expansive, impossible to ignore.

Streaming culture altered that rhythm. Today, some of the most resonant music in Indian storytelling does not announce itself. It appears like memory. It travels like thought. It carries the texture of a private playlist.

And increasingly, that sound is being shaped by independent musicians.

Across the past few years, Indian OTT series have begun to trust indie music with the emotional interior of story. Not as an accessory, but as narrative substance. The shift feels both contemporary and overdue. It reflects a country where audiences are no longer passive listeners, but intentional curators; where headphones have become environments, and where intimacy has replaced spectacle as the dominant emotional currency.

Streaming stories have simply begun to sound like the people watching them.

When indie sound becomes the emotional script

In Netflix’s Class, the soundtrack behaves like a secondary narrative. Songs by artists such as Faizan & Natiq, Zahra Paracha, Janoobi Khargosh, Sammad, 3BHK and Ezzyland do not merely signal mood, they articulate the fragile interiority of adolescence. The music feels confessional, unfinished in the most human way. It is not “placed” into the show so much as absorbed into its bloodstream.

Mismatched, particularly in its later seasons, inhabits a similar sonic register. The work of Ruuh, Joh, Vamsi Kalakuntla, Pina Colada Blues and others shapes a world that feels globally fluent yet rooted in unmistakably Indian emotional vocabulary. These songs carry the cadence of private listening. They do not comment on the scene. They complete it.

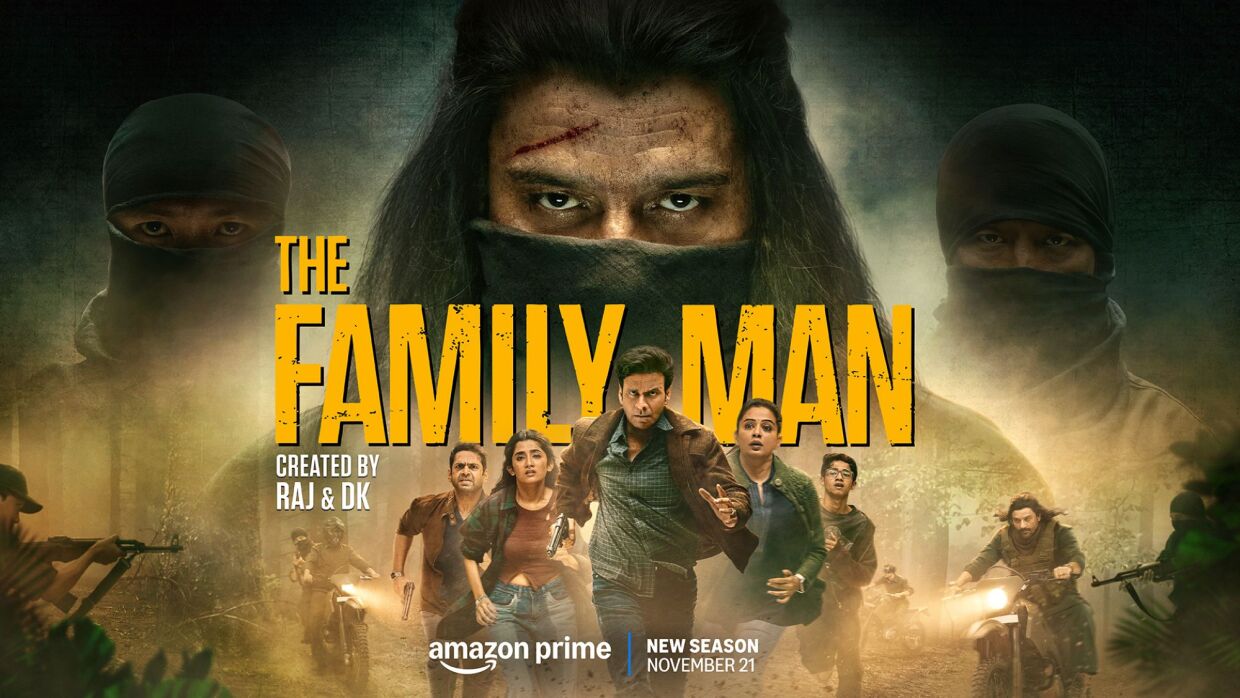

Elsewhere, The Family Man constructs a musical landscape that moves fluidly across languages and regions. Independent voices including Fiddlecraft, Swarathma, Bindhumalini Narayanaswamy, Prakash Sontakke, Brodha V, Aabha Hanjura — create a soundtrack that feels geographically expansive and emotionally precise. It is a portrait of India drawn through sound.

Bandish Bandits dissolves the border between classical tradition and independent musicianship altogether. Artists such as OAFF, Savera, Jhalli, digV, Prithvi Gandharv and Suvarna Tiwari remind audiences that classical discipline is not archival material, it is a living language capable of modern conversation.

In Chamak, music becomes narrative terrain rather than supporting detail. Punjabi folk, hip-hop, pop and independent sound function as cultural identity rather than decoration — the series is scored not around its world, but from within it.

Even mainstream-oriented storytelling as in The Fame Game — finds space for indie-linked works such as “Duur” by Kamakshi Khanna & OAFF, signalling that independent voices are no longer peripheral to the screen, they belong at its emotional centre.

Earlier, Little Things had already prepared audiences for this shift. Singer-songwriter intimacy became the emotional grammar of contemporary relationships onscreen. A generation learned that vulnerability could sound like a single voice and a simple melody.

The pattern — now visible — is not stylistic. It is philosophical.

Independent music has become the place where Indian storytelling goes to say what cannot be spoken outright.

Why this music resonates now

Independent sound carries qualities that industrial music often cannot, restraint, texture, quietness, imperfection. It sounds like proximity. It sounds like someone thinking. These are exactly the qualities that modern streaming narratives increasingly require.

Audiences, long accustomed to constructing identity through playlists, recognise authenticity when they hear it. Indie music does not seek to overwhelm the frame. It allows stories to breathe.

And sync, when done with care, becomes an act of alignment rather than insertion. The music does not illustrate emotion. It becomes its vessel.

The ecosystem beneath the sound

What makes this moment culturally meaningful is not only that independent artists are being heard, but that infrastructure now exists to support them.

Platforms that work with large, diverse communities of indie musicians — such as Hoopr, with its network of over 1,500 artists across India, form part of the unseen architecture enabling this exchange. They provide curation, rights clarity, and ethical licensing frameworks that allow independent work to travel safely into mainstream storytelling.

Without this scaffolding, the movement would remain fragile — dependent on chance discovery rather than sustainable practice. With it, independent sound becomes a viable cultural resource rather than a precarious one.

The result is a rare equilibrium: storytellers gain access to a broader and more authentic sonic vocabulary, while artists retain voice, dignity and continuity.

A redistribution of authorship

This shift is not an anti-Bollywood narrative. It is a widening of the lens.

The authorship of sound in India is being redistributed, from a singular pipeline to a constellation of independent creators whose work carries the emotional weather of the country in all its nuance, contradiction and multilingual richness.

As streaming continues to define how India listens to itself, independent musicians are no longer at the margins of cultural production. They are quietly writing its emotional core.

And supported by ecosystems designed to protect, elevate and connect their work, they are finally being heard — not as an alternative, but as a truth.